- Trends

- Posts

- Anatomy of a Hospital Financial Downturn

Anatomy of a Hospital Financial Downturn

How a provider system goes from making a margin to racking-up losses

A sizable chunk of our projects in 2023 and now in early 2024 have been focused on margin improvement for health systems, hospitals, and medical groups.

Even the healthcare providers that are nonprofit (as 60% of US hospitals are) need to be able to operate at a positive margin, unless they have sustainable outside funding from donations or another type of sponsorship.

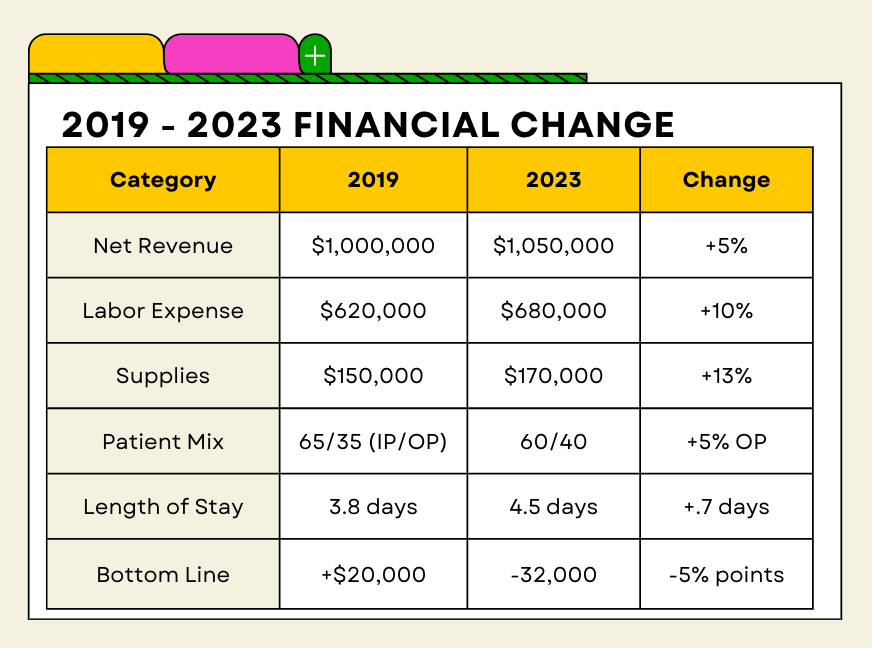

In a scenario that is pretty indicative of what I am seeing across the industry, I created a 2019-2023 financial story for “General Hospital.” While this hospital is fictional and so are the numbers, this story is very similar to several I am seeing…. and the numbers aren’t that far off from some real-life examples.

2019 to 2023: From 2% positive margin to -3% negative margin

The 5-point swing in margin, over the four years we have just had, is actually pretty typical. In many cases, providers bottomed-out in late 2022 or early 2023 and have seen some level of margin relief since, albeit slow.

Few are back to the margin levels of 2019, and the ones that are got there by taking some very intentional actions. “Waiting it out” has not been a viable strategy.

Let’s take a look at how the hypothetical-but-realistic General Hospital swung from a positive to a negative margin.

Yes, these figures are a little over-simplified and would not stand up to an audit as-is, but you can see the major drivers of how General Hospital swung from a positive to negative margin.

Let’s take a look at each category.

1. Labor Expense, up 15%

For General Hospital, I pegged Labor expenses at a 15% increase. Honestly, it could be a lot higher. I’ve seen labor increase by more than 30% over a four-year period in some markets.

The spike in labor expenses has subsided for many, but that doesn’t mean it has gone down. It is still elevated from where it was in 2019. Driven by a wave of departures right when additional staff were needed for Covid-19, some called it the perfect storm. The tight US labor market meant that almost anyone could find another job down the street, or outside of health systems.

Experienced nurse and clinician retirements spiked as well, with those people being replaced by newer staff who didn’t have the same broad skillset.

The decrease in available staff caused the chain reaction of needing to hire more expensive contract labor (e.g. travel nurses) for key functions, further raising the price of labor.

We are seeing healthy clinical pay raises again this year of around 8%, with non-clinical roles seeing more like a 3% bump. In most cases, these raises merely keep the provider comparable to their market pay.

What to do about it?

Many organizations took a hard look in 2023 at how they use contract labor — travel nurses, long-term contractors, etc. If that labor was being used in a way that wasn’t financial sustainable, they considered repositioning services.

A promising thing that came out of the labor cost spike was a refocus on retention, and making the organization a great place to work. Retaining talent is always less expensive than recruiting replacement talent.

We have also helped organizations be more sophisticated about scheduling and coverage. There is actually a pretty good AI use case emerging for ensure you have just the right amount of clinical coverage, given the patient schedule for any given day.

2. Supplies, up 10%

Supply costs, even rising at the rate of inflation (which is on the low-end of the range,) have added a material expense increase to most client health system. For organizations who have a higher expense line, those that are more procedurally-based, this figure can really add up.

It is an area where tight operations can keep a grip on the rate of price inflation. Negotiating good terms with suppliers and aligning around a few products (versus unlimited product options) can help an organization drive better pricing as the buyer, but that involves some clinical agreement on which products should be the chosen ones.

What to do about it?

Supplies are one of those area where a strong period of analysis and renegotiations can yield relatively fast results. Pharmacy and purchased services (e.g. cafeteria services, IT services) should not be overlooked.

If an organization has a culture of strong clinical leadership and alignment, zeroing in a few select products to use rather than a broad array of them can improve your leverage as a buyer.

More broadly, rethinking the way supplies are managed in an organization - from distribution to removing shadow buying operations to inventory levels - will move the needle too.

3. Patient Mix Shifts

In the analysis of General Hospital, the patient mix shifted from inpatient to outpatient. Is this a good or bad thing? It depends.

Outpatient care is typically less-expensive than inpatient care, but that is admittedly a very broad-brush statement. More care in an outpatient setting can be good for the healthcare system, as long a long-term outcomes are the same or better. The problem is that in many cases, the incentives around reimbursement for care might instead encourage inpatient care.

A subset of patient mix is payer mix too. If the patients are increasingly sponsored by government sources (self, Medicare, Medicaid) rather than commercial insurance (usually obtained through an employer), it is a financial hit for that provider. Generally speaking, commercial insurance reimburses at about 130% of cost. Medicare at cost. Medicaid at 70% of cost.

What to do about it?

Case management within organizations has only become more important. Making sure that every patient is being cared-for in the right setting for them is paramount. Secondarily, the case management function can consider the resource allocation for each patient, ensuring efficient care.

If patients are moving from one setting to another, a provider needs to be sure that their reimbursement can follow. That means reviewing arrangements with payer and creating a win/win — fair reimbursement for lower-cost settings.

4. Length of Stay Up .7 Days

In our General Hospital example, length of stay increased by .7 days. That is a material increase, the type I saw everywhere during the past few years, and it has a domino effect throughout the hospital.

More staff coverage is needed if patients are staying longer, and as discussed earlier, those staff are more expensive than they used to be. If the hospital is full, the person staying .7 days longer in an inpatient bed probably creates a backup upstream, like in the ED or Observation areas. That, in turn, creates a ripple to patient scheduling. It is like a traffic jam, where the cause of the backup is actually 2 miles up the road.

What to do about it?

When we help clients with length-of-stay, we often find that improvements can be made in many small areas that add up, there is not one single change that solves it.

Discharge planning is incredibly important, as having a place for a patient to safely discharge to can make the difference between another night in the hospital or not. Scheduling and staff coverage is equally important — if a patient requires a specific test or clinician visit before being able to progress in their care, any delay impacts the entire length-of-stay. And then there is efficient housekeeping - and turning a bed around. You can’t admit a new patient into an unclean room.

More hospitals have a strong Command Center of sorts to really be air traffic control for the organization. The complexity of patient flow throughout a facility, considering the unique treatments for each and the number of different clinicians involved, is considerable.

Conclusion

This anatomy of the General Hospital financial picture is just one example. Other providers might be suffering financially for a multitude of other reasons.

My main point is that the potential causes of financial challenges are many, and there is usually no single silver bullet for fixing them. While we have a pretty good idea of where to look for improvement opportunities, every client is very different.

Can General Hospital get back to breakeven? Yes. I’m sure of that. But it doesn’t happen overnight, and there isn’t one easy fix to do it.

Recommended Reads / Listens

Like many of you, I’m intrigued by the General Catalyst acquisition of Summa Health in Ohio. It is the most prominent private equity (or in this case, VC) acquisition of a nonprofit health system I’ve seen.

This Q&A with Case Western’s J.P. Silvers on the deal provides an interesting local analysis.

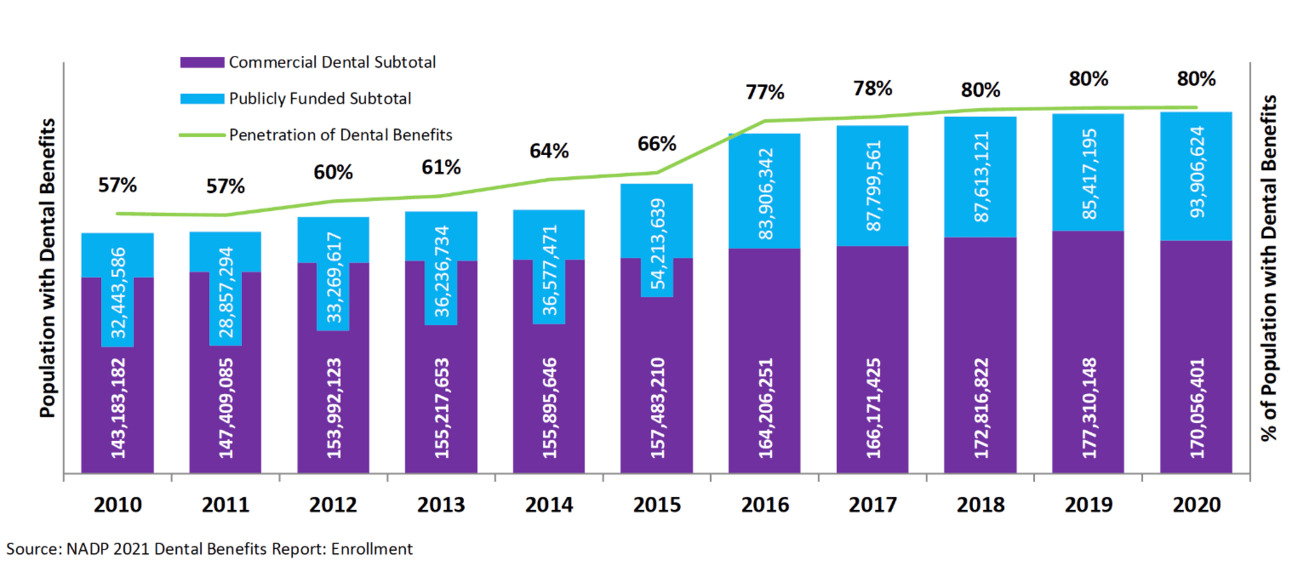

Chart of the Month

I don’t do a lot of work with dental providers, but have been hearing more about dental offices that don’t accept insurance. You can still use your insurance, but they aren’t filing the claim for you. You pay the dentist upfront and then get reimbursed later.

It got me wondering what population of the U.S. has dental coverage. Turns out it is stuck at about 80%. That compares to about 92% who have medical coverage.